Following Sixt’s withdrawal from Drive Now, Sixt is launching a new car sharing brand. Sixt Share is the name of the new service, which has been available for a few weeks, initially in Berlin and now also in Hamburg.

A newspaper report made headlines yesterday, according to which not only general vehicle availability and the location of the car but also information about the customer should play a role in pricing.

In particular, Chief Strategy Officer Alexander Sixt is quoted as saying that customers who want to rent a car with the Sixt app on an iPhone may be shown a different price than customers who use the same app on an Android smartphone. The exact location where the customer is currently located can also drive the price up or down: Someone walking out of a Chanel shop is likely to get a higher price than someone coming out of an outlet shop.

After an outcry, particularly on Twitter, @SixtDE rowed back a little and clarified that prices can vary depending on time and local demand, but that end devices or personal data are “not the decisive factor”.

UPDATE: Sixt is even clearer in an email that also reached me. According to this, SIXT share “does not use any personal data, such as location data from an individual user’s smartphone, when setting prices.”

Of course, data protection concerns have also been raised in some cases. But are these concerns justified? Is a service provider allowed to set its prices more or less freely based on the individual information of potential customers? And if so, under what conditions?

Freedom of contract applies

First of all, freedom of contract applies in Germany, and Sixt is also free to set its prices. Sixt does not have to offer everyone the same price all the time. It is true that there is a ban on discrimination in certain areas of public life. § Section 19 of the General Equal Treatment Act (AGG)prohibits discrimination on grounds of race, gender and age, among others. However, the standard only applies if the AGG applies at all. The prerequisite for this, however, is that one of the constellations defined in Section 2 (1) AGG applies. However, Car-Sharing does not fall under this, so that a general equal treatment requirement does not exist for Sixt.

Data protection prohibition principle

Legal problems with the individualisation of prices are therefore primarily posed by data protection law. In fact, Art. 6 Para. 1 of the not-so-new General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) stipulates that personal data may only be processed if there is a legal justification for doing so.

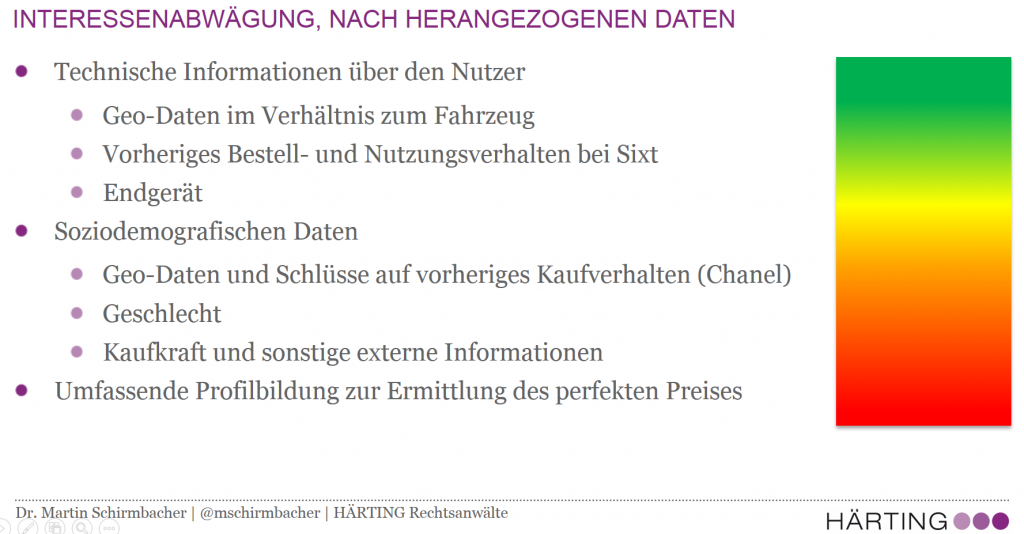

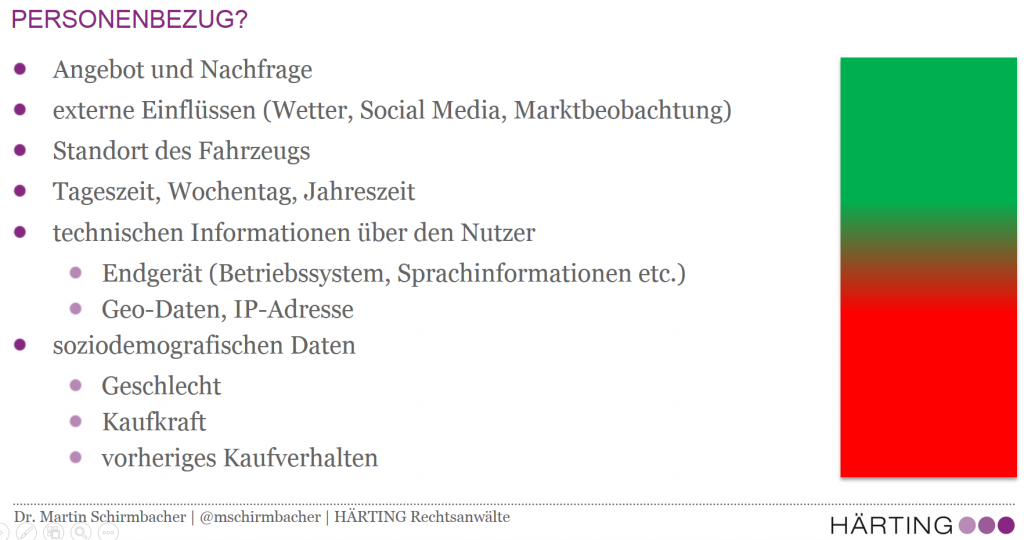

The current relationship between supply and demand or the location of the vehicle is not personal data. However, the user’s end device, its geo-data and previous usage and driving behaviour do constitute personal data. Incidentally, this also applies if the customer’s name does not play a role when the car is ordered, but the data is only collected pseudonymously.

In any case, a legal basis is therefore required for the use of such information for pricing. In particular, a justification pursuant to Art. 6 para. 1 sentence 1 lit. f GDPR and the legitimate interests of the company can be considered here. Only if it is concluded that justification is not possible does the question of the necessity of consent arise.

In any case, a legal basis is therefore required for the use of such information for pricing. In particular, a justification pursuant to Art. 6 para. 1 sentence 1 lit. f GDPR and the legitimate interests of the company can be considered here. Only if it is concluded that justification is not possible does the question of the necessity of consent arise.

Legitimate interests and reasonable expectations

Legitimate interests and reasonable expectations

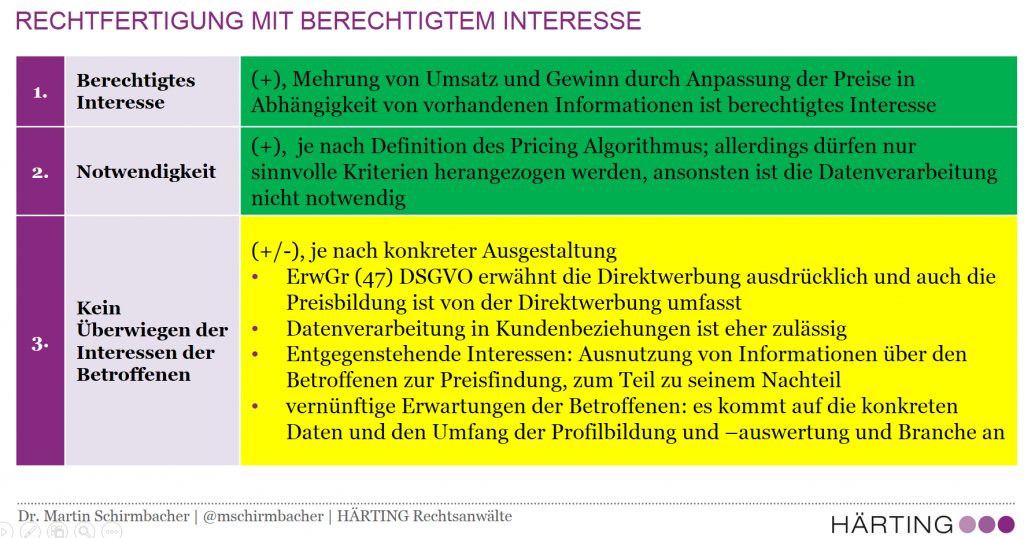

If data processing for the purpose of pricing is to be justified on the basis of the provider’s legitimate interests, there are three requirements:

- There must be a legitimate interest in the first place. This can be any legitimate interest, in particular increasing sales through intelligent prices and maximising profits through higher prices where possible.

- The data processing must be necessary to realise the interest. This means that not just any data may be processed, but only that which is actually useful for pricing, whereby the provider has a certain amount of room for judgement here.

- Finally, it must be examined whether the interests of the customers concerned in not having their data processed for the purpose of pricing outweigh the interests of Sixt. This depends on the specific details. This cannot be said in general terms. The law also refers to the reasonable expectations of customers. If everyone knows what data is being processed, the company’s interests will prevail in case of doubt. If, on the other hand, the customer cannot really know what data is being used for pricing, their interests will tend to prevail and data processing will be unauthorised.

It therefore also depends on Sixt’s communication. As the service is designed in such a way that customers are actually constantly shown different prices, it is clear to users that there is in any case a dynamisation of prices. If it is clearly communicated (and not just in the small print) that other factors are also included in the pricing, customer expectations will also extend to this. The fact that the operating system or previous offline purchases (at Chanel) play a role is probably rather surprising.

The data protection authorities take a much more critical view of profiling and in some cases already require consent for this. However, this goes far too far and has no basis in the GDPR.

In any case, comprehensive profiling and the determination of an ideal price for the specific customer based on an unmanageable number of factors is critical. Such extensive profiling is hardly permissible without consent. In this respect, the reference by Chief Strategy Officer Alexander Sixt to artificial intelligence and the proud announcement of the renunciation of segment data protection laware the most problematic.

Consent as an alternative solution

Consent as an alternative solution

If the balancing of interests shows that certain data may not be used for pricing, there is still the option of asking the customer for consent. This must be transparent. In particular, the customer must have a chance to understand which data processing processes they are specifically consenting to. Furthermore, consent must not be included in the small print of the general terms and conditions or data protection provisions. Sixt would be well advised to obtain this consent separately.

It is questionable whether consent should also be linked to the use of the service in general. This is a (further) unresolved GDPR issue. Properly understood, the GDPR does not contain a general prohibition on linking. Rather, when considering whether consent has been given voluntarily, weight must only be given to the fact that the contract cannot be concluded without consent. In this case, consent should therefore be invalid in case of doubt. However, if voluntariness is taken as the real yardstick, it could be argued that there are other car-sharing services and that nobody is forced to open a customer account with Sixt. Alternatively, Sixt could also make the consent optional, but point out that without individualisation of the prices, the price offered will generally be higher (insofar as this applies in practice).

Conclusion

As things stand at present, Sixt will not individualise prices. We will therefore not have clarity as to whether and under what conditions this is legally permissible. Setting up such a service is no child’s play in terms of data protection law, but neither is it rocket science. It requires careful consideration of the interests involved and clear user communication. Cleverly designed, consent is only required for data categories that are particularly unlikely to be used for pricing.

The difficulties in designing such a flexible pricing model in a socially acceptable way are obviously greater than the data protection problems.

Webinar on the legal aspects of dynamic pricing

If you would like to find out more about the legal aspects, you can listen to a webinar that my colleague Philipp Redlich and I held last month on the data protection and antitrust aspects of dynamic pricing.